The Truth About America: A History of Lynching Not Known By Many.

Never forget that these evil white people had children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren to whom they taught and handed down their disturbing, psychopathic, hateful, genocidal, spiteful, murderous, exploitative and sociopathic urges All you have to look at is the facial expressions of those wantonly killing people and then ask yourselves who the real terrorists are. If there was this much evidence against people of color, or of another religious faith, we would never be told, "That was such a long time ago...let's move forward".

Never forget that these evil white people had children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren to whom they taught and handed down their disturbing, psychopathic, hateful, genocidal, spiteful, murderous, exploitative and sociopathic urges All you have to look at is the facial expressions of those wantonly killing people and then ask yourselves who the real terrorists are. If there was this much evidence against people of color, or of another religious faith, we would never be told, "That was such a long time ago...let's move forward". When the Roman Empire was burning did you see the descendants of those thrown into the lion's den commiserating and sympathizing? No, they were celebrating. I am so tired of listening to the media describe one group as "Alt-Right/Neo-Nazis/Far-Right" (all so benign, pompous and official-sounding descriptions), while the other group castigated as "terrorists".

When the Roman Empire was burning did you see the descendants of those thrown into the lion's den commiserating and sympathizing? No, they were celebrating. I am so tired of listening to the media describe one group as "Alt-Right/Neo-Nazis/Far-Right" (all so benign, pompous and official-sounding descriptions), while the other group castigated as "terrorists".

In America they were praised and defended by President Tiny-fingered Dumbass, as exercising their freedom of speech rights.....really? You mean the same rights enshrined in the Constitution written by our slave-owning, genocidal, rapist founding fathers?

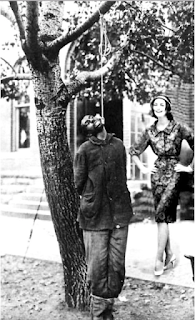

The following paragraph is taken from the book, "Without Sanctuary- Lynching Photography in America" by James Allen:

ジェームス アレン著アメリカの聖域ーリンチの写真の本から。

"According to the New York Times, "The suspect, indentified as Rubin Stacy, was hanged to a roadside tree within sight of the home of Mrs. Marion Jones, thirty year old mother of three children, who identified him as her assailant". Six deputies were escorting Stacy to a Dade County jail in Miami for "safekeeping". The six deputies were "overpowered" by approximately one hundred masked men, who ran their car off the road. "As far as we can figure out," Deputy Wright was quoted as saying,"they just picked him up with the rope from the ground. They didn't bother to push him from an automobile or anything. He was filled full of bullets, too. I guess they shot him before and after they hanged him. Subsequent investigation revealed that Stacy, a homeless tenant farmer, had gone to the house to ask for food; the woman became frightened and screamed when she saw Stacy's face". Time and again, we come across long hidden newspaper clippings with the inscription, "a white mob took him from county officials, lynched him, and riddled his body with bullets."

ヨークタイムズによると、「容疑者は、ルービン・ステイシー(Rubin Stacy)として容認され、3人の子供の30歳の母親、マリオン・ジョーンズ夫人の家で見えるように、路傍の木にぶら下がっていた。 6人の代議員がステイシーをマイアミのデイド郡の刑務所に護送して「保護」していた。アメリカをスーパーパワーにするために、アフリカから数百万人の黒人アフリカ人が拉致され、米国に持ち込まれ、アメリカが核兵器の力になる前に何万人もの黒人が殺され、去勢され、焼かれ、そして今日まで至る。

From 1889 to 1918, more than 2,400 African Americans were hanged or burned at the stake. Many lynching victims were accused of little more than making "boastful remarks," "insulting a white man," or seeking employment "out of place." They were hanged from trees, bridges, and telephone poles. Some were castrated, others burnt alive. Victims were often tortured and mutilated before death: burned alive, castrated, and dismembered. Their teeth, fingers, ashes, clothes, and sexual organs were sold as keepsakes. White-privileged terror continues till this day...perpetuated under color of authority, protected and state-sanctioned, enveloped in the latest so-called 'Alt-Right/Far Right/Neo-Nazi' administration, an euphemism for state-sponsored genocide....stop calling it by these cute-sie names. Call it what it is....terror, lynchings, murder, ethnic cleansing.....genocide.

From 1889 to 1918, more than 2,400 African Americans were hanged or burned at the stake. Many lynching victims were accused of little more than making "boastful remarks," "insulting a white man," or seeking employment "out of place." They were hanged from trees, bridges, and telephone poles. Some were castrated, others burnt alive. Victims were often tortured and mutilated before death: burned alive, castrated, and dismembered. Their teeth, fingers, ashes, clothes, and sexual organs were sold as keepsakes. White-privileged terror continues till this day...perpetuated under color of authority, protected and state-sanctioned, enveloped in the latest so-called 'Alt-Right/Far Right/Neo-Nazi' administration, an euphemism for state-sponsored genocide....stop calling it by these cute-sie names. Call it what it is....terror, lynchings, murder, ethnic cleansing.....genocide.

Before he was hanged in Fayette, Mo., in 1899, Frank Embree was severely whipped across his legs and back and chest. Lee Hall was shot, then hanged, and his ears were cut off. Bennie Simmon was hanged, then burned alive, and shot to pieces. Laura Nelson was raped, then hanged from a bridge.

“Here is a strange and bitter cry!"

[Lyrics of the famed song: “Strange Fruit” as recorded by the late Billie Holiday]

[Lyrics of the famed song: “Strange Fruit” as recorded by the late Billie Holiday]

As the dust of the Civil war settled, many Blacks mistakenly thought they saw an era of prosperity and hope. This dream was cut drastically as a concerted effort was begun by whites to destroy any advances which Blacks had made for themselves. This effort was extremely successful in removing Blacks from the many state and federal offices which Reconstruction had allowed them to hold. But for evil, vile and hateful white people, this was not enough. The architects of the revived South needed something more to further the cause of white supremacy and Black oppression. Out of this need, the era of Jim Crow was born with its “separate but equal” claims. And with it came a wave of violence against America’s newest citizens. The social atmosphere of white supremacy which the African slave trade had started, and continued under Jim Crow, soon became a tide of hatred. Bolstered by the idea of the inferiority of Blacks and the so-called protection of “white womanhood,” whites saw it as nothing to trample Blacks in a storm of violence.

As the dust of the Civil war settled, many Blacks mistakenly thought they saw an era of prosperity and hope. This dream was cut drastically as a concerted effort was begun by whites to destroy any advances which Blacks had made for themselves. This effort was extremely successful in removing Blacks from the many state and federal offices which Reconstruction had allowed them to hold. But for evil, vile and hateful white people, this was not enough. The architects of the revived South needed something more to further the cause of white supremacy and Black oppression. Out of this need, the era of Jim Crow was born with its “separate but equal” claims. And with it came a wave of violence against America’s newest citizens. The social atmosphere of white supremacy which the African slave trade had started, and continued under Jim Crow, soon became a tide of hatred. Bolstered by the idea of the inferiority of Blacks and the so-called protection of “white womanhood,” whites saw it as nothing to trample Blacks in a storm of violence.

These attacks included lynchings, burnings, shootings, boilings, and race riots, and though the majority of this violence took place in the South, the North was by no means immune. For more than a century, angry whites made the life of Black America a continuous nightmare.....and it continues till this day, albeit, under color of law and authority.

Lynching is the practice whereby a white mob, (usually several hundred, or thousands of persons), takes the law into its own hands in order to kill a person accused of some wrongdoing. The alleged offense can range from a serious crime like theft or murder to a mere violation of local customs and sensibilities. The issue of the victim’s guilt is usually secondary, since the mob serves as prosecutor, judge, jury, and executioner. Due process yields to momentary passions and expedient objectives.

Lynching is the practice whereby a white mob, (usually several hundred, or thousands of persons), takes the law into its own hands in order to kill a person accused of some wrongdoing. The alleged offense can range from a serious crime like theft or murder to a mere violation of local customs and sensibilities. The issue of the victim’s guilt is usually secondary, since the mob serves as prosecutor, judge, jury, and executioner. Due process yields to momentary passions and expedient objectives.

Clergymen and business leaders often participated in lynchings. Few of the people who committed lynchings were ever punished. What makes the lynchings all the more chilling is the carnival atmosphere and aura of self-righteousness that surrounded the grizzly events.

Railroads sometimes ran special excursion trains to allow spectators to watch lynchings. Lynch mobs could swell to 15,000 people. Tickets were sold to lynchings. The mood of the white mobs was exuberant--men cheering, women preening, and children frolicking around the corpse.

Photographers recorded the scenes and sold photographic postcards of lynchings, until the Postmaster General prohibited such mail in 1908. People sent the cards with inscriptions like: "You missed a good time" or "This is the barbeque we had last night."

Lynching received its name from Judge Charles Lynch, a Virginia farmer who punished outlaws and Tories with "rough" justice during the American Revolution. Before the 1880s, most lynchings took place in the West. But during that decade the South's share of lynchings rose from 20 percent to nearly 90 percent. A total of 744 blacks were lynched during the 1890s. The last officially recorded lynching in the United States occurred in 1968. However, many consider the 1998 death of James Byrd in Jasper, Texas, at the hands of three whites who hauled him behind their pick-up truck with a chain, a later instance.

Lynching received its name from Judge Charles Lynch, a Virginia farmer who punished outlaws and Tories with "rough" justice during the American Revolution. Before the 1880s, most lynchings took place in the West. But during that decade the South's share of lynchings rose from 20 percent to nearly 90 percent. A total of 744 blacks were lynched during the 1890s. The last officially recorded lynching in the United States occurred in 1968. However, many consider the 1998 death of James Byrd in Jasper, Texas, at the hands of three whites who hauled him behind their pick-up truck with a chain, a later instance. Mob lynchings were a common form of death for young Black men who were beaten, stoned, dragged through the street and then burned alive by onlookers, their body parts later sold as souvenirs, which was often the custom. The idea that most of these men were charged with the rape of white women is a false one. Their alleged crimes were numerous: using offensive language; bad reputation; refusal to give up a farm; throwing stones; unpopularity; slapping a white child; not moving off the sidewalk fast enough at the approach of a white person; and stealing hogs to name a few.

Mob lynchings were a common form of death for young Black men who were beaten, stoned, dragged through the street and then burned alive by onlookers, their body parts later sold as souvenirs, which was often the custom. The idea that most of these men were charged with the rape of white women is a false one. Their alleged crimes were numerous: using offensive language; bad reputation; refusal to give up a farm; throwing stones; unpopularity; slapping a white child; not moving off the sidewalk fast enough at the approach of a white person; and stealing hogs to name a few. In East Texas a black man and his three sons were lynched for the grand crime of “harvesting the first cotton of the season”. Less than 15% of those lynched were ever charged with rape. Fewer were ever proven.

In East Texas a black man and his three sons were lynched for the grand crime of “harvesting the first cotton of the season”. Less than 15% of those lynched were ever charged with rape. Fewer were ever proven.

It should be remembered that it was not only Black men who were killed during this era. The lynching of Mary Turner best illustrates this. Turner, a pregnant Black woman, was lynched in Valdosta, Georgia in 1918. Turner was tied to a tree, doused with gasoline and motor oil and burned.

As she dangled from the rope, a man stepped forward with a pocketknife and ripped open her abdomen in a crude Cesarean operation. A news reporter who witnessed the killing wrote:

“Out tumbled the prematurely born child. Two feeble cries it gave and received for the answer the heel of a stalwart man, as life was ground out of the tiny form”.

There was a Silent Protest March of 1917 against lynching which featured the famous banner, “Mother, do lynchers go to heaven?”

In East Texas a black man and his three sons were lynched for the grand crime of “harvesting the first cotton of the season”. Less than 15% of those lynched were ever charged with rape. Fewer were ever proven.

In East Texas a black man and his three sons were lynched for the grand crime of “harvesting the first cotton of the season”. Less than 15% of those lynched were ever charged with rape. Fewer were ever proven.

It should be remembered that it was not only Black men who were killed during this era. The lynching of Mary Turner best illustrates this. Turner, a pregnant Black woman, was lynched in Valdosta, Georgia in 1918. Turner was tied to a tree, doused with gasoline and motor oil and burned.

As she dangled from the rope, a man stepped forward with a pocketknife and ripped open her abdomen in a crude Cesarean operation. A news reporter who witnessed the killing wrote:

As she dangled from the rope, a man stepped forward with a pocketknife and ripped open her abdomen in a crude Cesarean operation. A news reporter who witnessed the killing wrote:

“Out tumbled the prematurely born child. Two feeble cries it gave and received for the answer the heel of a stalwart man, as life was ground out of the tiny form”.

There was a Silent Protest March of 1917 against lynching which featured the famous banner, “Mother, do lynchers go to heaven?”

Ida B. Wells was one of the most outspoken crusaders against lynchings, burnings, and other acts of white on Black violence. For forty years she rallied her cause in both America and Europe. A radical for her times, Wells worked feverishly to dispel the myth of the sex-starved, white skin-lusting, black rapist. This was an act which put her life in danger time and time again. No pacifist, she stated defiantly that the greatest deterrent against lynching was for every Black man to keep a Winchester rifle at his window. Ida B. Wells wrote several long and detailed studies on lynchings which are still regarded as some of the best works on the subject even today.

Often the word ‘riot’ conveys in one’s head the idea of Black urban residents rebelling as seen since the 1960s. But riots were a part of America long before Blacks decided to take part. Throughout the United States, riots erupted as angry white citizenry of all classes took to the streets to terrorize and attack Blacks.

They took place in Memphis, Chicago, Wilmington, and elsewhere. Entire prosperous Black districts were destroyed in Oklahoma, Texas, Florida and hundreds of other predominantly Black cities, by jealous whites. These white riots were numerous both in the North and South and were often helped along by the local police or militia.

Many lynchings of course were never reported beyond the community involved. Furthermore, mobs used especially sadistic tactics when blacks were the prime targets. By the 1890s lynchers increasingly employed burning, torture, and dismemberment to: prolong suffering and excite a festive atmosphere among the killers and onlookers.

The Census Bureau estimates that 4,742 lynchings took place between 1882 and 1968 (the real numbers are estimated to be three to four times higher). Between 1882 and 1930, some 2,828 people were lynched in the South; 585 in the West; and 260 in the Midwest. That means that between 1880 and 1930, a black Southerner died at the hands of a white mob more than twice a week. Most of the victims of lynching were African American males.

Here is another little known Black History Fact. This information is in the African-American Archives at the Smithsonian Institute. Although not taught in American learning institutions and literature, it is in most Black history professional circles and literature that the origin of the term: ‘picnic’ derives from the acts of lynching African-Americans.

This is where individuals would: ‘pic’ a Black person to lynch… and make this into a family gathering. There would be music and a ‘picnic’. (‘Nic’ being the white acronym for: ‘nigger’).

Scenes of this were in the movie Rosewood. The black producers and writers should have chosen to use the word ‘barbecue’ or ‘outing’ instead of the word ‘picnic’.

Scenes of this were in the movie Rosewood. The black producers and writers should have chosen to use the word ‘barbecue’ or ‘outing’ instead of the word ‘picnic’.

To attempt to tie lynchings to family outings, where food was served, is to misunderstand the real nature of these events. Rather, they were outbreaks of mass white hysteria, and attempts by groups of Whites to terrorize and brutalize the entire Black communities where they occurred.

Often, they were motivated by alleged acts of violence by Blacks against Whites, alleged disrespect and other breaches of Southern racial ‘etiquette’, and on many occasions, victims were chosen at random. Although women and children were frequently present, it is more accurate to view these events as collective psychotic behavior, rather than family outings. Lynching had become a ritual of interracial social control and recreation rather than simply a punishment for crime.

Often, they were motivated by alleged acts of violence by Blacks against Whites, alleged disrespect and other breaches of Southern racial ‘etiquette’, and on many occasions, victims were chosen at random. Although women and children were frequently present, it is more accurate to view these events as collective psychotic behavior, rather than family outings. Lynching had become a ritual of interracial social control and recreation rather than simply a punishment for crime. “If it is necessary, every Negro in the state will be lynched”, declared James Vardaman while he was Governor of Mississippi (1904-1908). “It will be done to maintain white supremacy.”

“If it is necessary, every Negro in the state will be lynched”, declared James Vardaman while he was Governor of Mississippi (1904-1908). “It will be done to maintain white supremacy.”

When I was a boy growing up in New York, the word lynching was hardly ever mentioned. My parents only said these “mean” acts happened in the country (rural areas) with white men in white gowns (the KKK). In all my schooling, through high school, and even in college, lynching was never part of a lecture or connected with American history. I knew of the word, lynching, but schools were loathe to mention it, and never, ever examine the scope of this violent, hateful act. Luckily I had a few elders in my African family who made it their duty to tutor me from a young age as to the true homicidal nature of white American vile, privileged and genocidal pervasiveness.

On Thursday, January 13, 2000, an article entitled, “An Ugly Legacy Lives on, Its Glare Unsoftened by Age,” by Robert Smith was published in the New York Times. This excellent article revealed a world not known by many Americans living today. Without my explaining here, it should be read by all persons, especially as it pertains to race and hate. Without understanding this past evil history, many cannot understand why hate is on the rise today or why the descendants of the victims of these actions are still mad till today.

It turned out that an exhibit of rare collected photo postcards were on display featuring lynchings as they took place in America from 1883-1960. I saw this exhibit. It was on view at the Roth Horowitz Gallery in New York City until February 12, 2000. This small gallery took in only about fifteen people at a time, and the line was long. Watching the viewers as they exited revealed what was inside: people with tears, some with anguish, some looked surprised with the horror they had seen.

This New York exhibition presented the collected photocards of Mr. James Allen, a white Atlanta resident who, for fifteen years, sought out these images of racial horror and self-righteous vigilante acts as rare finds. Since most of these photocards were kept as “keepsakes” by some families, Mr. Allen had to solicit ads for purchase. He paid from fifteen dollars to as much as thirty thousand dollars for individual cards. The sixty photo postcards and other material were temporarily housed in the library at Emory University to allow scholars to have access to it, but are now being held by their owner at withoutsanctuary.org.

This book, "Without Sanctuary: Lynching photography in America" (by James Allen, Hilton Als, Leon F. Litwack, with a forward by Congressman John Lewis; Twin Palms Publishers, 2000), is a new, startling book on this shocking topic of lynching in America. This book is an extension of the exhibit held at the Roth Horowitz Gallery and the collected photo postcards of Mr. James Allen of Atlanta, Georgia. Pages of actual real life lynchings are captured with photos and dates with explanatory texts about where these dastardly acts occurred. Mr. Allen says, “Without Sanctuary is a grim reminder that a part of the American past we would prefer for various reasons to forget we need very much to remember.”

This book, "Without Sanctuary: Lynching photography in America" (by James Allen, Hilton Als, Leon F. Litwack, with a forward by Congressman John Lewis; Twin Palms Publishers, 2000), is a new, startling book on this shocking topic of lynching in America. This book is an extension of the exhibit held at the Roth Horowitz Gallery and the collected photo postcards of Mr. James Allen of Atlanta, Georgia. Pages of actual real life lynchings are captured with photos and dates with explanatory texts about where these dastardly acts occurred. Mr. Allen says, “Without Sanctuary is a grim reminder that a part of the American past we would prefer for various reasons to forget we need very much to remember.” The book is a vivid account of the existence of terrorist lynching on American soil. On view in the book are ninety-eight plates of lynchings and the victims and the people surrounding the actual executions. A few were white; a few were women; but most were African-American men used as prime targets for lynch mobs. To see this book is to try and understand, but it is not for the squeamish viewer or persons not able to transcend reasons why these acts should never have happened.

The book is a vivid account of the existence of terrorist lynching on American soil. On view in the book are ninety-eight plates of lynchings and the victims and the people surrounding the actual executions. A few were white; a few were women; but most were African-American men used as prime targets for lynch mobs. To see this book is to try and understand, but it is not for the squeamish viewer or persons not able to transcend reasons why these acts should never have happened.

Sources, References and Further Reading:

"About Lynching" by Robert L. Zangrando, John F. Callahan, and Dickson D. Bruce, Jr. Modern American Poetry : An Online Journal and Multimedia Companion to Anthology of Modern American Poetry. Urbana, IL : Department of English of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2002.

"The aesthetics and politics of the crowd in American literature" by Mary. Esteve. Cambridge, U.K. ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2003.

"American lynching : a documenatry feature" by Gode Davis and James M. Fortier. Herndon, VA : Bitter Fruit Productions, 2005. (This documentary explores racist events and attitudes indigenous to the Northern and Southern states that either condoned or condemned lynching as a practice.)

"American Negro short stories" by John Henrik Clarke. New York : Hill and Wang, 1966. PS647.A35C55 1966x (Includes “The lynching of Jube Benson” by Paul Laurence Dunbar)

"Anatomy of a lynching: the killing of Claude Neal" by James R. McGovern. Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, 1982.

"And the dead shall rise : the murder of Mary Phagan and the lynching of Leo Frank" by Steve Oney. New York : Pantheon Books, 2003.

"Anti-lynching crusaders helped free our country" by Philip Dray. Newsday, A39 (741 words), June 15, 2005.

"An apology for old form of terror: Senate expected to vote tomorrow on resolution regarding its failure to help end practice of lynching" by Martin C. Evans. Newsday, A34 (600 words), June 12, 2005.

"At the hands of persons unknown: the lynching of Black America" by Philip Dray. New York : Random House, 2002.

"The awful truth: a photography exhibition unearths the painful history of lynching in America" by Danny Postel. Chronicle of Higher Education, 48(44):A14 (3 pages), July 12, 2002.

"Black manhood on the silent screen" by Gerald R. Butters. Lawrence : University Press of Kansas, 2002. PN1995.9.N4B88 2002 (Includes “Oscar Micheaux: From Homestead to Lynch Mob).

"Call for reconciliation : Minister attacked by Klansmen seeks understanding as alleged mastermind in triple killing faces trial" by John Moreno Gonzales. Newsday, A07 (733 words), June 13, 2005.

"Crime, but no punishment: Georgia town is still divided over the murders of four blacks nearly 60 years ago" by Tina Susman. Newsday, A30 (1633 words), March 30, 2005.

"Dangerous liaisons : gender, nation, and postcolonial perspectives" by Anne McClintock, Aamir Mufti, and Ella Shohat. Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 1997. JC312.D36 1997 (Includes “On the threshold of woman’s era : lynching, empire, and sexuality in Black feminist theory” by Hazel V. Carby)

"The Duluth Lynchings Online Resource: a collection of historical documents relating to the tragic events of June 15, 1920" by Scott Ellsworth. Minnesota Historical Society. St. Paul, MN : The Society, 2003 (This web site facilitates access to over 2,000 pages of scanned documents to provide an in-depth and scholarly resource of primary source materials on the subject, designed also for those unfamiliar with this tragic event).

"The Duluth Lynchings Online Resource: historical documents relating to the tragic events of June 15, 1920" by Scott Ellsworth. Journal of American History, 91(1):349-350, June 2004

"Ebony rising: A short fiction of the greater Harlem Renaissance era" by Craig Gable. Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 2004. (Includes “Lynching for profit” by George S. Schuyler)

"Elite Georgia’s dark secret" by Linda Kulman. U.S. News & World Report, 135(13):49, (800 words), Oct 20, 2003 (1915 lynching of Leo Frank)

"Etiquette, lynching, and racial boundaries in southern history: a Mississippi example" by J. William Harris. American Historical Review, 100(2):387 (24 pages), April 1995.

"Exorcising blackness : historical and literary lynching and burning rituals" by Trudier Harris. Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 1984.

"F.B.I. discovers trial transcript in Emmett Till case" by Shaila Dewan and Ariel Hart. New York Times, A14 (917 words), May 18, 2005.

"A festival of violence: an analysis of Southern lynchings, 1882-1930" by Stewart Emory Tolnay and E. M., Beck. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1995.

"The first Waco horror : the lynching of Jesse Washington and the rise of the NAACP" by Patricia Bernstein. Houston, TX : 2005.

"Fresh outrage in Waco at grisly lynching of 1916" by Ralph Blumenthal. New York Times, A26 (1598 words), May 1, 2005.

"Gender, class, race, and reform in the progressive era" by Noralee Frankel and Nancy Schrom Dye. Lexington, KY : University Press of Kentucky, 1991. (Includes “African-American women’s networks in the anti-lynching crusade” by Rosalyn Terborg-Penn)

"Go down, Moses: the miscegenation of time" by Arthur F. Kinney. New York : Twayne Publishers ; London : Prentice HallInternational, 1996. PS3511.A86G6349 1996 (Treatment of lynching in the William Faulkner work "Jasper, Tex., and the ghosts of lynchings past". New York Times, A26 (576 words), Feb 25, 1999).

"Judge Lynch: his first hundred years" by Frank Shay and Arthur Franklin Raper. Montclair, NJ : Patterson Smith, 1969.

"The killing season: a history of lynching in America" by Philip Dray. The New Crisis, 109(1):41 (3 pages), January-February 2002.

Excerpt from “At the Hands of Persons Unknown: the Lynching of Black America”

"Kin disagree on exhumation of Emmett Till" by Gretchen Ruethling. New York Times, A3 (357 words), May 6, 2005.

"The legacy of a lynching" by Robert F. Worth. American Scholar, 67(2):65 (13 pages), Spring 1998.

“Like a violin for the wind to play: lyrical approaches to lynching by Hughes, Du Bois, and Toomer" by Kimberly Banks. African American Review, 38(3):451 (15 pages), Fall 2004.

"Local sequential patterns: the structure of lynching in the deep South, 1882-1930" by Karherine Stovel. Social Forces, 79(3):843 (14134 words), March 2001.

"Lynch-law: an investigation into the history of lynching in the United States" by James Elbert Cutler. New York : Negro Universities Press, 1969.

"Lynch Street: the May 1970 slayings at Jackson State College" by Tim Spofford. Kent, OH. Kent State University Press, 1988.

"The lyncher in me: a search for redemption in the face of history" by Warren Read. St. Paul, MN : Borealis Books, 2008.

(Chronicles the author’s experiences with having discovered his great-grandfather’s role in the Duluth lynchings of 1920 and his subsequent search for the descendants of the victims).

(Chronicles the author’s experiences with having discovered his great-grandfather’s role in the Duluth lynchings of 1920 and his subsequent search for the descendants of the victims).

"Lynching" by John Simkin. Spartcus Educational.

"Lynching in America: carnival of death" by Mark Gado. TrueTV Crime Library : Criminal Minds and Methods. New York : Turner Broadcasting System, [2005?].

"A lynching in the heartland: race and memory in America" by James H. Madison. New York : Palgrave, 2001.

"The lynching of persons of Mexican origin or descent in the United States, 1848 to 1928" by William D. Carrigan. Journal of Social History, 37(2):411 (29 pages), Winter 2003.

"Lynching victim is cleared of rape, 100 years later" by Emily Yellin. New York Times, Section 1, 24 (912 words), Feb 27, 2000 (Story of falsely accused rapist Ed Johnson from Chattanooga, Tennessee)

"Masculinity: bodies, movies, culture" by Peter Lehman. New York : Routledge, 2001. (Includes “Lynching photography and the ‘black beast rapist’ in the southern white masculine imagination” by Amy Louise Wood)

"Media, process, and the social construction of crime : studies in newsmaking criminology" by Gregg Barak. New York : Garland Pub., 1994. P96.C74M43 1994 (Includes “Communal violence and the media : lynchings and their news coverage by The New York Times between 1882 and 1930” by Ira M. Wasserman and Steven Stack)

"Minstrel show; or, The lynching of William Brown (The Plays of Max Sparber)" by Max Sparber. Minneapolis, MN : 1998 (Retells the story of the real-life murder of an African-American man in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1919, through the narration of two fictional African-American blackface performers.)

"The murder of Emmett Louis Till, revisited": by Brent Staples. The New York Times, A16 (912 words), Nov 11, 2002 (New documetary film may cause the 1955 Mississipi case to be reopened).

"The NAACP crusade against lynching, 1909-1950" by Robert L. Zangrando. Philadelphia : Temple University Press, 1980.

"The Negro holocaust: lynching and race riots in the United States, 1880-1950" by Robert A. Gibson. Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. New Haven : Yale University, 1979 ; posted 2005.

Comments

Post a Comment